Episode 6: Steve Solomon Covers Soil Remineralization & Nutrient Density

"The problem is not that there is residues of pesticides in our food, the problem is that there's only residues of nutrition left in our foods.”

~Steve Solomon

Transcript:

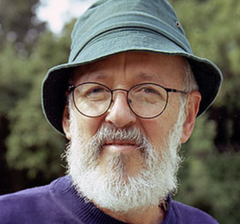

Tad: Welcome to the Cannabis Cultivation and Science podcast, I'm your host Tad Hussey of KIS Organics. This is the podcast where we discuss the cutting edge of organic growing from a science-based perspective and draw on top experts from around the industry to share their wisdom and knowledge. Today we're honored to be interviewing Steve Solomon all the way from Tasmania. Steve is the author of numerous books, most notably 'Gardening West of the Cascades' and 'The Intelligent Gardener'. Can we start off today talking about your own personal journey, and how you came to write ‘The Intelligent Gardener’ which focuses on soil remineralization and nutrient density?

Steve: You know, you're asking me to tell you about my whole life and there's not enough time to do that, so I'm going to condense things to the best I can, and if I wander you stop me. I wanted to live a life where I work as little as possible, and I conceived the idea that if I could produce as much of my own stuff as I could, and I wouldn't have to earn money or pay taxes on it, then I might get a better lifestyle.

So we moved to Los Angeles, sold the business, bought five acres in Oregon that looked real pretty to us. I knew because I’d read all I’ve got through organic gardening literature, I had even subscribed to organic gardening magazines and I’ve read their books, and I knew this was true that I could take any old clay pit or gravel heap and turn it into a garden of Eden, as long as I put enough compost in the ground and maybe some lime.

So I found this beautiful green hillside in Oregon then, in springtime. I could afford it, there were just five acres of bare land with some little Douglas fir trees self-seeding on it. It was flat enough that I could put in the garden, and moved on to it and I put in the big garden and started to eat out of it, and then one thing after another happened and then a few years later, I found myself in the seed business. Not knowing how to do it, not knowing how to make any money off it, it took me two years being in the business before I learned to make a little bit of a profit while basically taking every bit of money I had left which, by the way, was $13, 000 dollars!

Tad: Now, you're referring to Territorial Seed there?

Steve: That's right! Territorial Seed Company. Yeah, it got capitalized with all the $13,000 dollars that I still had.

Tad: It’s a highly successful seed company, yes?

Steve: Yeah, it became that, but in the first few years, I had no idea how to run a seed business, you know, I had to learn. But I tried to do it honestly so I put in a trials ground. If you find a seed company that doesn't have a trials ground, go the other way. They're just not somebody I want to admire or do business with. I won’t use a lot of other language.

So, there I was, with a business that was not making me money, truly the first year I made nothing, took nothing out of it because I just needed everything to try to do the next year. The next year, I actually managed to take $4,000 dollars out of the business and pretty much lived on that $4,000 dollars, and the year after that I took $7,000 dollars out of the business so then it got better, then it went fourteen, twenty-eight, you know, forty. I started doing well but in the beginning, it was pretty difficult so what kept me going was the trial ground.

Now I had a lady friend at that time who became Mrs. Solomon. Her name was Isabelle Moser, and she went to Great Oaks School of Health and she was a naturopath who practiced medicine without a license and have always avoided going to prison for any of the crimes that she was committing, like practicing medicine without a license or having somebody with cancer who was dying and come stay with her and try to recover, and they died anyway and then, you know, there’s manslaughter charges.

And that’s all, that sort of thing. I don't know if you're aware of how alternative health is suppressed in the United States, but she was a very brave outlaw, and Isabelle told me that I would be a lot healthier the more vegetables that I ate and the fact that I didn't have any money and had all these trials was really a great opportunity for me and all I really needed to do was live on vegetables almost completely and then when I did that the healthier I’ll become.

Oh, well that seemed to make sense. So, I did that, and the more I did that the more unhealthful I became and Isabelle came and moved in with me and she started eating the same vegetables and the more she ate them the less healthful she became although she was an extraordinarily healthy woman. She began to experience brittle hair and thin fingernails, that sort of stuff and I started to have teeth that got a bit wobbly, sorta had off days and felt grouchy and lost energy and things started to seem difficult, life seemed stressful.

So after about four years in the business, I was making enough money and things were organized well enough that we took off six months, and I just didn't do trials that year, and we went away at the end of the spring and didn't come back until after Christmas. We went to Fiji and that's where I had this illumination where we just started eating the fruits and vegetables in the market in Fiji, in Suva, and we didn't go to the tourist Fiji, we went to the capital city of Fiji and lived with the Fijian people and did what you do in Suva, that's not a place most tourists went.

The market there had all the usual European vegetables, as well as a whole lot of tropical stuff and we ate all that stuff. We found it all tasted really good, we started eating okra too and we had plenty of beans and we ate cooked greens of various kinds. Anyway, we had more or less the same kind of diet we'd always been eating, and my teeth got tight to my jaw and her fingernails got hard and we felt her hair got beautiful and we had much more energy and we felt much better and I wanted to find out what was going on. So, I made some inquiries and found out that all those vegetables that we've been eating came from the Sigatoka valley, which was an hour and twenty minutes drive out of Suva.

So we rented a car for the day and drove up to the Sigatoka Valley and I ran ahead and booked myself in to have a visit with the research station that they had up there in the valley. They showed me around and told me how the farmers grew vegetable crops, and that they never use fertilizer, and that they've grown vegetables for 75 years in that valley, European type vegetables, and they had never used any fertilizer in 75 years but they did use a lot of pesticides. I think he said the reason they had to do that was when you grow European French beans [snap beans you call them in the United States] in the tropics, there’s a lot of things that want to eat them, you know, but they were grown without fertilizer.

The reason that it worked is that the watershed of the Sigatoka River is an area of extraordinarily highly mineralized rock or the type that’s called ultrabasic igneous rock and it basically means it's just chockablock with plant nutrients, cations, with calcium and magnesium and potassium and iron and zinc and manganese and copper, it's just loaded with all that stuff, it makes soils that tend to be neutral to slightly alkaline which is why they call it ultrabasic igneous rock.

Well, that stuff comes down the Sigatoka River as silt, and about every three years there's a cyclone. What they call a cyclone there we call a hurricane and the Sigatoka floods, and it covers the entire valley floor and no one has a house on the valley floor except the government research station which is upon sort of a mount. Everybody who farms there lives on a little bit on the slopes outside the valley. Anyway, it deposits its silt and every three years or so there's a large deposit of freshly ground rock dust of the most mineralized salt you could ever want to have and during the rainy season. It has a 2-season climate, there is a dry, mild season when the weather's like a beautiful, mild summer day in Washington, you know it's 78 degrees and the sun is shining and you know, the only differences that in the dry season their nights would never go down below about - I don't know, 65 F, something like that, they're always mild and short-lived weather. Then, it gets rainy and hot and humid and it gets so humid and so hot that all those vegetable crops die of disease and the fields get taken over by the weeds, and the weeds grow mid-chest high for about five months and then it stops raining and they get in there and plow the weeds under and they decompose rapidly and that's the organic matter. And I think the decomposition of the organic matter also helps release minerals out of the rock dust and they plant their vegetable seeds and they grow beautiful crops and they taste really good and made us incredibly healthy despite the pesticide residues. I had to figure that out because I believed in organic stuff, I was a believer in all that Rodale bullshit, right.

Tad: So Steve, let me pause you, so just to clarify; the soil where all the vegetables that you were eating at your time in Fiji was grown in a particular valley where no fertilizer was being used whatsoever, but -

Steve: That's right.

Tad: - they did use a variety of chemical pesticides that did not fit with your current organic dogma or ideas?

Steve: That's right. And my belief system at that time would have told me that those pesticides were bad for me and that there was no way I could possibly be healthy if I’m eating food with pesticide residues on them and I came away from there with a different opinion which was after I thought it over and you asked me about it a few years later. I think I would have told you, and a lot of audiences, that I came up with the wonderful line that I used to use when I lectured, I said: “the problem is not that there are residues of pesticides in our food, the problem is that there are only residues of nutrition left in our foods”.

Tad: So you're not claiming that pesticides are necessarily good, but rather that the level of mineral content in our vegetables is so depleted because our soils are so depleted that it's affecting our nutrient levels and our health way more than these trace elements of pesticides that may be left on the vegetable itself?

Steve: Yeah, well the trace elements wouldn’t hurt us but the residues of the pesticides – the residues of the pesticides -

Tad: Yes?

Steve: - they’re an insult to our body, they are poisons and our bodies are designed to deal with insults and poisons. The better nourished the body is and the healthier the body is, the better it is at handling that sort of stuff so a very well-nourished body would be much less affected by pesticide residues generally speaking, on average, we're talking statistics here not about any individual case.

Tad: Sure. So just to bring it back to your time in Fiji. So you discovered this knowledge and then winter came and you had to head back to Oregon at that point.

Steve: That's right.

Tad: And how did that guide your gardening or your experiences moving forward after you left Fiji?

Steve: Well, it didn't really nail home for about a year because we came back from Fiji and we felt really good. We were enjoying life, I mean we were youngsters, we were your age and not much older, you know we still didn’t have much sense.

Tad: [Chuckles]

Steve: And so we just went back into it, and Isabelle was an athlete, she did triathlons and got into her athletics, so then I got back into my business of writing and after about a year we noticed that her fingernails were getting soft again and her hair was deteriorating and my energy level was dropping and my positive attitude was harder to maintain some days and my teeth were starting to worsen. And I said shit, you know. It's the food we’re eating, it's that trials ground that we're eating off of or what's wrong with it? You see, I didn't really know. I had been using a sort of like a primitive approach to complete organic fertilizer at the time, I had already evolved that and there was a ratio of limes. I always - I wanted to have a ratio of calcium to magnesium that was 7:1 - so I tried to put in a mixture of dolomite and ag lime to come up with about 7:1 because I didn't know anything about soil testing, I figured well the best thing I can do is put it in at 7:1

Tad: Sure.

Steve: And not to put it into too fast, you know, I got a lot of information and I started doing research and - I mean if you want I can tell you about all the mistakes I made along the way but -

Tad: Well, what I would like to maybe focus in on then is; so you started researching this and I know from reading your book, more than one time actually, that you focused on some of the work by Price and the dental records, which I think is really fascinating and then you also started looking into remineralization with some of the work by William Albrecht.

Steve: That's right.

Tad: Maybe if you could touch on both of those findings briefly that would be wonderful.

Steve: Yeah. Let me just sort of put a warning note there that I wrote this book called “Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades” and it's been through several editions and every one of those editions except one has been a complete rewrite. It’s a totally different book every single time it comes out with the same title, okay? And so some of the earlier editions have versions of complete organic fertilizer or make assertions about the nature of the soils or what you should do that today I would consider incorrect, so I contradict myself from book to book. Yeah so I just don't want people to get stuck if they've got an older book or believe something that I said back in 1988 or 1992, that was only from a very limited partial understanding of the whole thing, it took a long time before I got it all worked out.

Tad: Sure. I would say that's one of the things that I really appreciate about you as an author, is that you are open-minded to learning new things and changing your mind on subjects as you become more experienced or more educated on a particular subject.

Steve: Thank you. I think that's one of my strong points too or weak points, anyway the older I get the more I realize I'm not so damn smart, you know.

Tad: So can you tell our listeners a little bit about what you learned from Price in particular?

Steve: Weston Price, gosh! His book, “Nutrition and Physical Degeneration” is, in my opinion, the most important book that was written in the twentieth century and I mean you can even put Einstein in there, top 10 or all those or any other book you come up with because see Price did something for us that's actually priceless. He documented the existence of groups of people that no longer are the way he documented them.

In the 1930s, there still were places on this planet that were so isolated that the people who lived there completely ate the food that they got there and they didn't bring any food, they were poor usually and very simple. They lived in hard to get at places that nobody wanted, you know, a little remote valley somewhere or someplace we had to trek in Pakistan through passes, it was frozen in ice and snow 9 out of 12 months of the year you know and go up so thin you could hardly walk with the danger of slipping off the edge and dying every 300 meters, you know on a really dangerous trail for a couple of three days of this to get there, places like that.

So Price had heard about these places and he was interested in dental health from the point of preventative dentistry, he spent his whole life trying to work in there. He had failed completely as a research scientist and he never could figure out how to prevent people from having bad teeth. He'd see occasional people who had really good teeth but why? Is it just their genes? Is it where they grew up? Is it what’s in their diet? There was no way to know and he said the only way we're ever going to sort this is if we have a control group and we don't have a control group. Maybe these people are our control group, he says I hear that these people in these remote places have extraordinary good health and almost perfect teeth, all of them, let's go and have a look.

So he and his wife organized these basically treks into remote places with the assistance of the local medical authorities usually because Price was quite well known globally as a medical-dental researcher, so he went and visited these people and he did this over three years, very extended trips by ship of course to different continents and then journeys to these places, and he went with - I don't know how many people he went with, I'd love to know the details of how he organized his things but he took a lot of photographs, very high quality black and white pictures, he had a lab within where - he didn’t analyze the soils, they had only primitive knowledge of nutritional aspects of food but what Albrecht did know how to find out – excuse me, what Price knew how to find out was the mineral content of the food.

Vitamins were just being discovered, there weren’t sure what they were exactly, you know their chemical formulation was not known, all the B. vitamins were just sort of lumped together, I think they were called B. vitamins because they were water-soluble but they didn't know one from the next but Price was able to ash the food. He could take a sample of the food and heat it up until he burned off all the carbon and he has was some ash, and then he could use simple analytical chemistry and say in that ash there was so much potassium, so much phosphorus, so much calcium, so much magnesium, and that's what he did.

So he collected that data from several dozen groups of people and took photographs of – often quite old people with all their teeth and their jaw and obviously in good health and documented all kinds anecdotal evidence and looked at questions like; are the people in this remote place so healthy because they have special genes and not like the people down in the valley who don't have those genes and that's why they have good teeth and the people in the valley have rotten teeth? No, that's not what happened actually, he got documentation that young people from the remote place with perfect teeth went down to the town to have an adventure and stayed there for three years, ate the food down there and came back home with a mouthful of decay.

And then he'd find out many of those people that carried the dental cavities actually had healed and had a scar over with naturally occurring enamel although but it was obviously scarred tissue and the body that healed those cavities, isn’t that amazing? All those people were taking two, three, to four times the mineral nutrition of the average American in the 1930s.

Tad: So basically the quality of the food that they were growing from a mineral perspective was much higher and therefore their own health which was reflected in their dental records and their dental health was much higher as well so they didn't have a lot of the tooth decay and problems that you were seeing in other areas of the world at that time.

Steve: Another way to say that would be that the designer of the human body designed it so that if it was adequately nourished it would keep all of its teeth for its entire lifetime and they would be in perfect condition, tightening the jaw and the only thing that would affect them would be eating a whole lot of abrasive stuff that wore them down in which case they also have the ability to replace that hard coating on the outside if you’re well-nourished enough which is how those cavities heal or as you played sports you know, you got a few teeth knocked out. But other than that, that’s the bodies design, that's how it's made, the body made to last - I don't know, 110 years, okay let's say, on average which means that if we all have perfect nutrition for a few generations, because just one generation all of a sudden starting on perfect nutrition does not make perfect babies. Actually the nutrient density of mothers has to increase and it takes several generations for a line of females to develop sufficient nutritional reserves that they can then form a perfect fetus and then nourish it with breast milk. That fetus would then go on to have on average less than a hundred and ten years probably.

Tad: Steve, just to bring this back to plants. Obviously re-mineralizing soils are important from a nutrition perspective in terms of our own human health, what are you finding though in terms of the health and growth of your plants by adding these minerals back into your soil?

Steve: I started intentionally re-mineralizing a year before “The Intelligent Gardener” came out so that was - I mean it was kind of like I was dealing with trace elements and really with the kind of remineralization that I'm advocating these days. So ever since then my food has tasted better every single year, year on year and it's still happening, not all of it but some of the crops, some kinds of vegetables the flavor improved a great deal for the first two years and then it sort of stabilize and it's very nice.

That would be stuff that's shallow root crops like lettuce because I got the topsoil re-mineralize d first to see but the trouble is how do you re-mineralize the next six inches down or the next foot down because vegetables well put roots down a lot further than most people realize if they can and if they don’t encounter a lot of nutrition down there they don't do as well. This is especially true of root crops like carrots and parsnips and beetroot. These crops and all the chicories, they all feed in the subsoil. Chicories, as you know, are root crops that just make edible leaves in the same way that parsley is a root crop that makes edible leaves. The chicory; let me tell you what happened to my chicory. We like to eat endive but it has a problem, it tends to be bitter and it has another problem, in the wintertime, in the humid weather and the cool humidity of our autumn in winter, it develops a leaf disease that tends to cause rot spots and it can get worse and worse until it rots back to a stump and it can get so spotted with these things you don't want to eat it anymore and it'll kill it eventually in the wet weather, it doesn't happen anymore.

I thought that was the nature of endive you know, and it was hard to grow in the humidity of the winter and you put the plants further apart and you do everything possible to increase air circulation and it doesn't rot as quickly but in a wet winter you're just going to lose it, I thought that was the nature of endive, now it doesn’t happen anymore. Now it’s just less so that disease doesn't happen anymore because when the endive starts to try to feed down 2 feet down, it's finding nourishment now, it just took years to leach it down there.

Tad: So you’re seeing an increase in disease resistance essentially.

Steve: Huge, at the same time there’s another problem with endive, it’s bitter. Well at the same time that the endive had stopped having problems with the spots on the leaves, it stopped being nearly as bitter and started actually being so sweet and you can eat it like lettuce.

Tad: So improving the quality of the flavors and odors of your given crop essentially.

Steve: A great deal. People who eat with us are just gobsmacked; they’re all good at food tastes. They don't have a clue how good vegetables can taste until they taste my vegetables, or how satisfying they can be and how much less inclined we are to eat other things than vegetables because the vegetables are just so rich, I don't know how to put it.

Tad: Sure everyone has had the experience of eating conventionally grown or a hydroponic tomato from a grocery store or going out to a real farm and picking one off a vine and the difference in the flavor is dramatic.

Steve: Right, if you could go to that farm and walk rows of the variety trial and taste thirty different kinds of tomatoes all at the same time, you’ll find there was a lot of difference and that some of them had a lot better flavor than others but if you could take and put a couple of parallel rows with the same varieties and you fully remineralize one row and you didn't with the other, the plants might not look all that different but you would surely notice the taste difference in the same variety from the two different soil circumstances.

Another thing that happens with remineralized food, it doesn't mold after you harvest it, you know, if you just let it sit out on the counter, it doesn't grow mold it just sort of slowly loses its moisture and shrinks a little bit, it stops being quite as crisp. It just sits there you know and it stores a whole lot better if you put it in the fridge.

Tad: Okay so can you touch a bit on how a grower or gardener would use some of these principles in terms of adding these minerals back into their soil? So I know that in your book you talked a lot about soil testing, can you describe that process to someone that would be new to the subject?

Steve: Yeah but I want to back up one step, I want to talk about targets. What are we trying to accomplish? The soil test is just the tool that we use to accomplish it with but I think we want to start to talk about what it is you're trying to do. Albrecht worked out the basics of this stuff, he worked out roughly the relationship, the levels of calcium to magnesium and potassium and phosphorus that a plant needed to produce a lot of protein and to be very healthy such that the livestock that eat it would also be very healthy but he didn't finish the work. He probably didn't because the soil testing procedures available at that time weren't sophisticated enough to do soil testing inexpensively. It would have cost a great deal to determine how much copper and zinc and manganese and stuff there was in soil or boron, you know, in those days. It could have been done I think but now it’s easy. Now for $14 dollars and a little bit of postage, you send 60 grams of soil to a lab in Ohio, I can get an accurate reading of the levels of all those elements in the soil.

Tad: Now you're referring to Logan Labs with that?

Steve: No actually I'm not. I'm talking about one called Spectrum Analytic.

Tad: Okay. Logan is $25 dollars for their standard soil test I believe.

Steve: Logan's presentation, the way they give you the information, is probably a little more friendly to an amateur otherwise it's not a lot of difference. I mean they come up with roughly the same kinds of numbers, they may differ but if they differ it's all because all the numbers from one maybe ten percent higher than all the numbers from the other and in practicality doesn't really matter, what really matters is the relationship between all those numbers and they’ll be the same for both laboratories.

It took the work of a whole lot of really smart farm advisors who sort of took Albrecht as a springboard and they developed a philosophy of fertilizing soil called ‘base cation balancing’ and the idea is to bring the levels of the plant nutrients up to a point and a balance that produces optimum health in those that eat the fruit and at the same time produces a very good yield and very healthy plants that don't have as much trouble with insects and diseases and all that stuff which is all very good and then also, you don't get that kind of result unless the land is healthy so part of the process is maintaining enough organic matter of soil, okay?

So it's a sort of regenerative or positive sort of agriculture where you're building real soil fertility and better health of the entire ecosystem to produce a result in the crops that you want. The trouble with that approach is that it does not appeal to the greedy, selfish farmer who just wants the make the biggest bottom line they can because the economic logic of the farmer is sustained profit, is the result of how much they can short cut the inputs. The more they can reduce the cost of inputs, the more money they can make.

Tad: So these soil tests traditionally are focused around minimums for yield, isn’t that correct? So where they're not talking about necessarily looking - their recommendations are not necessary for optimal plant growth or health or soil building but rather minimum that still allow for no plant deficiencies.

Steve: Yeah the word is ‘sufficiency’, okay. There are two philosophies about how to fertilize; there's the economically rational philosophy and then there is the ethical philosophy you might say. So the economic rationalists, they just want to make sure that there is enough of all the plant nutrients that the crop will produce a lot and enough is defined this way; putting any more in will not result in any increase in yield that is in any way related to the cost of putting more in.

So now as we put it in, until the yield peaks out and then you don't put it anymore, because it's not economically rational, you're better off to use your money for something else. So they target lower levels than somebody who is being ethical about their food on what to target. They want to make sure that there’s enough copper there, that the plant isn’t obviously copper deficient, not having any gross copper symptoms but the idea that having ten times that amount of copper in the soil might do something to the total balance of nutrition in the crop, more protective substances, more phytonutrients, more of that stuff that the plant uses to protect itself against insects and diseases that then when the human eats the plant also protects us against diseases and things as you say, they don't think about that stuff.

Tad: Sure. Now, most of our listeners are cannabis growers, you have a high-value crop here until where you can put more into your soil and you can build your soil, so how does that influence your - say your recommendations or how you would treat the soil knowing that you can afford to throw a little bit more at the crop in terms of minerals and nutrients?

Steve: Well listen, you're just very lucky in this respect that you asked me this question because now there is no way that I could talk about me growing cannabis here in Tasmania because it isn't legal.

Tad: Sure.

Steve: But it just so happens that I have a friend who has a license to grow hemp and we are growing hemp here in Tasmania now and it's a burgeoning industry that the government is actually trying to forward. They have a certain problem with it in that they also want to have total control over it, they want to make sure that nobody does an extraction from hemp and get CBD oil out of it without them calling it medicine and have it in their system.

But in any case, he asked me if I would do some soil testing for him and make recommendations about what to do to grow good hemp crop and I've done that. So I got some idea, the kind of nutrition hemp would need if you were thinking about it from the point of farming it. You know, raising it by the acre or planning it like wheat.

So hemp needs - hemp, first of all, it makes a lot of fiber. Plants growing vegetatively like hemp, they probably need twice as much potassium as most vegetable crops, and they take a lot of it out of the soil. If somebody would be growing it in the same place they would have to - and we're actually taking the material out of the field then they should realize they're taking a lot of potassium when they're they take it out of the ground. Hemp uses a lot of manganese, for some reason it just draws a lot of manganese, it helps the plant be more healthy, it uses a great deal of it.

Tad: That brings up an interesting question for me, Steve.

Steve: Yeah.

Tad: Well sort of a two-part question. So my first question is; traditionally people on these tests aim for P to equal K - phosphorus, and potassium to be equal. Now what you're suggesting with cannabis sort of fits what some of the findings that I'm having as well saying that we want to run potassium possibly a lot higher than we would with phosphorus.

Steve: That's right.

Tad: Do you have any other comments on that?

Steve: Yeah I would think that's right. There's one thing about my experience that may be different than with the cannabis growers and that is; I'm talking about growing stuff in the soil, in the field where you’ve got several feet of growing media beneath your feet, a lot more root zone than you can put into a small pot. If you start putting plants in synthetic growing media indoors, now you're dealing with the medium that doesn’t have any exchange capacity usually and this is an interesting conversation. If you're growing in something that has no buffering capacity, do use that term ‘buffering capacity’?

Tad: A little bit, this may be getting a little technical for some of the listeners but yes, so the soils that we manufacture here at KIS Organics, they range in CEC or cation exchange capacity, I'd have to look at a test, I don't have one in front of me but I think there are around - anywhere between twenty to thirty.

Steve: That's quite high but I would like it very much off later if you share with me maybe on another day even, what it is you use to get that kind of exchange capacity in a synthetic medium, I would imagine you used vermiculite and charcoal and really good compost but I can't think of anything else. Anyway, if you can load up your exchange capacity in your growing medium with the plant nutrients that it needs then I'd say you'd want it to test kind of the same way as soil that you’d want to grow a tomato plant in, with the exception that you'd want potassium up a bit higher and then with another exception too, if you're not feeding the crop mostly with soluble fertilizers, see if you've got a growing medium in a container that has no buffering capacity, then basically you're growing on hydroponics.

Tad: Yeah.

Steve: Even if it looks like soil, even if you've got living compost in it, even if there is, you know, an ecology living in it, if most of the nutrition the plants are getting is coming in the water that you're feeding the pot with then it's hydroponics. I’m not totally sure what the proper levels would be to try to duplicate that with dry fertilizers and that kind of stuff we use in the soil. So out in the field, we have another thing or a pot maybe if you have a large container with a lot of growing medium that has an exchange capacity over 20, then you could mix the nutrients into the medium and they would then go on to the exchange sites and sit there waiting for the plant to draw them off, that would be a much better way of going about it, I think the plant would get quite stable nutrition that way. So I would fertilize that stuff more or less like I fertilize the field.

Tad: So you would top dress with these dry amendments or nutrients over the course of the plant's life like you would in your garden, is what you’re suggesting?

Steve: Yeah I put as much of that as I could into the soil without making it too hot and then I add more on the surface as the plant grew. From what I know about growing cannabis, you actually want to feed the crop quite differently depending on whether flowering or whether it's vegetating.

When it's vegetating, you want to feed it lots of nitrogen and lots of potassium and a fair amount of phosphorus and all the trace elements. We'll get into this when we talk about foliar feeding and all that sort of thing. Anyway, you really want that heavy and then when the plant goes into bloom, it's not making a lot of vegetation anymore. Growers need to understand that mostly what nitrogen is for is to make chlorophyll.

Chlorophyll is a protein. It's nitrogen-rich so when the plant’s constructing leaves, then it needs a lot of nitrogen and then the leaves then they dark green and they have a lot of active chlorophyll in them and they make a lot of sugar and they do a good job.

When the plane starts to bloom, you know it stops making leaves and starts making flower mass. This mass doesn’t have very much chlorophyll in it at all. Cannabis growers are trying to breed the leaves out of these flower structures as much as possible because they are less harsh when you smoke them.

They talk about - don’t they talk about a ratio kind of like calyx to leaves and that sort of thing? They want lots and lots of sigma and lots and lots of seed bracts but very little in the way of leafy structure, or am I wrong, Tad?

Tad: Yeah essentially they want the most viable part of the crop in most cases which is not the fan leaves, you know they want trichome density but then, when we're looking at that plant growth, you know bud formation and things like that, there are nutrients - certain nutrients that are tied to this but in this, an addition to just these macro or major nutrients that we're talking about right now that nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, sulfur, one of the things that I think that you have really promoted is adding in all these trace minerals so by getting these rock dusts into the soil, we're going to increase the terpene levels, the trichome density, the quality of the final crop while also increasing the overall health and yield of the plants.

Steve: Now actually Tad, there’s something that you could do could that it wouldn't be free for you to do it but you could answer a really major question for me, okay? Because you are using rock dust, right? I’ve always had a lot of reservations about rock dust.

When I lived in Oregon, there was a quarry into the old Cascades basalt and it was located right along Interstate 5 between Cottage Grove and Creswell Oregon and you could see it when you went the highway. They mine basalt for road base and things like that, crushed rock and you could get dust if you want it. You could just go there with buckets and at the base of the conveyor belt that those rock dust just piled up as deep as you want to shovel it up and take it away, they were just as happy to see you do that.

So I tried it and used a whole lot of it and didn't seem to do a great deal, didn't seem to make much difference that I could tell and I got an analysis of it, it actually has in it all of the trace elements that you want but when you analyze parts per million and then think about how are actually spreading and if I'm spreading a ton of rock dust and it's three parts per million zinc, well in a ton there's - what is that, is that a million, a million grams? Anyway, I think a ton is something like a million grams so if it's three parts per million that means that in a ton of that stuff I got 3 grams of elemental zinc, let’s say in a ton.

Now when I spread zinc sulfate I want to spread 7 pounds of elemental zinc on an acre and that's soluble so that goes out of zinc sulfate and it was into the soil solution and then it attaches itself under the cation exchange capacity if it’s not immediately picked up by a plant and it’s sitting there as available zinc to feed the crop and I put 7 pounds of available zinc basically into that field but into the furrow slice over the top of the top six inches of the soil.

If I put out a ton of rock dust, I'm putting I’d say 3 pounds are potentially available zinc then someday when the stuff completely breaks down, whenever that happens, so how much unavailable zinc would I have to put out to actually make 7 pounds of zinc available on the exchange side? When you start to ask that question it starts to look like we're talking 15, 20, 30, 40 tons of the acres.

Tad: I think I can give a little bit of input on this. So one thing I want to distinguish before we go too much further is that when we put out rock dust or we add alfalfa into our soil, we're not directly feeding our plant but rather feeding these microbes that are in the soil that are cycling these nutrients into a form that the plant can uptake. So another important aspect of gardening and growing and farming is that it is the microbial populations that we have in our soils and that's where high-quality compost becomes really important.

Steve: Right. I knew you were going to say that by the way. That’s also the party line of the rock dust people who are pushing rock dust and saying it's a solution to how they explained it and I've always had my doubts. I mean I'm from Missouri man, you’ve got to show me.

So what I'm saying Tad is you could show me. There is a way you could show me, it's really interesting. All you've got to do is have some tissue testing done. Take some of the nice leaves from some of the cannabis that you’ve been growing with this rock dust in the medium and send them off to a lab that does leaf analysis and find out if the levels of copper and zinc and manganese and boron in the leaves are what you want.

Tad: Unfortunately here in Washington there is no tissue testing as far as I'm aware of that's legal for cannabis. I believe maybe in Oregon it's possible but it's not something we can do yet.

Steve: Oh that’s right, you can't send the leaves to Oregon, can you? Not legally.

Tad: Yeah we definitely can't mail anything.

Steve: Alright so it's just not maybe possible to really answer this question here.

Tad: Well I think it is. So to give you a little more information, when we mix our soils we're putting in around a hundred pounds of minerals and nutrients per yard of soil, some very, very high levels of amendments, that that soil is going to actually heat up and thermally compost for at least two weeks.

Steve: Yeah.

Tad: While we're turning it and keeping it evenly moist before it'll even cool down to what we can plant into it so we're putting in very, very high levels of a lot of these nutrients in our soil.

Steve: Well this container, so if you put a plant in 50 liters of this material, that's a nice big pot, right? Not a 12-inch pot, say you put it into a 14-inch pot, yeah or something with a good volume of soil. Is there enough nutrients in there that you can go and plant from one end to the other or just nothing but water?

Tad: We found a 7-gallon container is probably the minimum and that's going to vary based on how long you’re vegging the plant before you flip it into flower but we are finding that yes you can go the full cycle. Now in a smaller container like a 7-gallon, we have a nutrient pack which is essentially the dry amendment that we put into our original soil mix that we will top-dress the pot and scratch into the surface, at the end of the first and the end of the third week of flower, just a half cup to a cup per plant as a way to help it get those nutrients by the time it's ready to finish.

What we're finding is growers that are doing raised beds indoors or giving the plant more soil as we discussed, they're able to - are able to grow larger, healthier crops because one thing you may not be aware of is that in the cannabis industry traditionally, what's happening is; a grower is bringing soil into an indoor facility, they are - maybe it's basement, maybe it's a garage, maybe it's an actual warehouse and then that soil is - well…. soil or perlite, whatever their media is I guess, is then fed with either bottled nutrients that are organic or ones that are ionic salts or you know, conventional, and then at the end of the cycle that soil that's typically grown conventionally with excessive nitrates and excessive phosphates is then put outside and disposed of because the salt levels are way too high, they can't reuse it.

Steve: Not without substantial leaching, I imagine anyway.

Tad: Yes so then that soil that's primarily - you know, let's say coco based or just perlite based is then dumped out and leaching into groundwater which is a whole another problem and they're having to buy and bring in new soil, a new bottle of nutrients and start over again. So what myself and others have been working on is essentially creating a living soil indoors over time by re-amending these larger containers every cycle in place so we don't have to move the soil in and out the facility and we have some growers that been using the same soil up to 5 years now by just adding back organic matter and adding nutrients back similar as you would find in nature.

Steve: Right. So if you did some soil testing on these containers soil at the end of every crop and got an idea of what was there already you could then use sort of like the Intelligent Gardener approach and figure out what they needed to put in there to bring it back into balance.

Tad: Yes though we do find that The Intelligent Gardener one doesn't allow for that higher potassium and a few other things that seem to be more specific to cannabis, what we do have lab tests or soil tests with Logan that show how these levels are varying every crop cycle based on the nutrients that we're putting in at the beginning of the cycle so we can see more or less what the plant is taking out of the soil over time. So I can I think start to address your rock dust question in that regard.

Steve: Yeah, you can. You can clear that off for me.

Tad: Because being an organic gardener, I don't feel comfortable adding a lot of these sulfates. So things like zinc sulfate or copper sulfate, I can't - I don't think I can add them into my soils according to NOP standards because they're not considered organic. Same with manganese sulfate, I would love to know a good organic form of manganese for example.

Steve: What is NLP?

Tad: The National Organic Program, so it's sort of the standard.

Steve: NOP, I misheard it. Here in Australia, organic certification agencies will allow the grower to use sulfate salts of trace elements, if a soil analyst, as determined by scientists, that these things are deficient.

Tad: That’s the same law here but as someone who is just making soils from container media, it's not something that I want to get into adding into my soil initially because of the fact it isn't considered you know completely organic.

Steve: Yeah.

Tad: Do you know of other sources for some of these? I know kelp meal is one that you talk a lot about and -

Steve: How would you feel about using chelated trace elements that instead of being copper sulfate were copper gluconate? People who use them say that you don't need to use much more than about half as much to have the same result.

Tad: Is that the Biomin copper that you're referring to?

Steve: Yeah, that’s a Biomin trace element.

Tad: You know I haven't looked into that product I believe it is OMRI certified though.

Steve: Yeah. So you might feel okay, you and your client base might feel okay about using that stuff. If it would be acceptable theoretically, I think you should experiment with it and see what it does for you, if anything.

Tad: Now do you know of a good source for manganese besides manganese sulfate? Well we- I know we touched on that a minute ago.

Steve: Not unless as a Biomin form of manganese, I don't know. That's another difficulty that I have. You see where I live, I’m way out of the end of a long supply chain and Australia is way out of the end of a long supply chain so you people in North America have a lot more materials and possibilities available to you than we do down here. As far as I know, I don't have any choice, if I want to add manganese, I need manganese sulfate.

Tad: So just to sort of summarize what we've been talking about a little bit here, for a grower to test his soil or test his container growing media, find out what those levels are based on a soil test, they can then go back and amend their soils properly to bring any levels that are low or bring everything into balance.

Steve: Yeah and let me - I got to stop you here a little bit. Going backward a few minutes, you could use the levels that are recommended in The Intelligent Gardener to grow cannabis, with the exception of potassium so you could still use the targets that Intelligent Gardener generates, let’s say for all the other elements, it's just that you probably want at least twice as much potassium as the Intelligent Gardener calls for.

Tad: I totally agree with that, we're finding the same thing with our trials as well here so that makes a lot of sense to me.

Steve: Yeah but the amounts of nitrogen, if you think about cannabis as a high demand crop during the time that it's in the vegetative growth and then as a very low demand crop when it's blooming, and make sure that during all of that time – see because low demand crops don't demand lower levels of trace elements or calcium, they just really need lower levels of nitrogen, because they're not making chlorophyll. They're still growing fast, they’re still building a lot of mass.

Tad: Just to clarify, so what you're getting at is essentially that because cannabis is an annual plant, an annual crop, it's going to naturally want to senesce or complete its life cycle and that's what the process of forming buds or flowers is and during that process, it doesn't need as much nitrogen because it's not trying to put on any vegetative growth.

Steve: That's right. In fact, it might need a third as much nitrogen or even a quarter as much nitrogen as it needed while it was growing new leaves.

Tad: Now on that subject, one thing that Jeff Lowenfels talks about it in his book “Teaming with Microbes” is that the plant is really in control of this process based on the exudates it’s putting out into the soil to control sort of the nutrient cycling and microbial loop, what's going on there in the area around the roots, do you have any thoughts or comments on that?

Steve: It's just the sort of gut-level feeling and I hope you take is the right way Tad, but you see, people who want to believe in organics, and I say ‘want to believe in organics’, and then they adjust things so that they make a good story, it's a good narrative, okay? And that’s what I think you're hearing there, and there is some truth to it and it does happen. I've been learning all kinds of things about how plants talk to the microbes in their root cells, get a collaborative relationship going on. I wouldn't mind talking about that it's really quite exciting information.

I’ve been finding out how to wind my plants up on another 25 or 30 percent more than they ever were before by foliar feeding them the same kind of elements that we've been talking about. I’ve discovered that plants cannot obtain all the nutrients that they could use if they could but get them, not out of the soil. It doesn't matter what you put into the soil, it doesn't matter how concentrated the soil is, the plant could use more of certain things at certain times and if it gets them, there's a dramatic improvement in the way that plant grows. The way you do that is with foliar feeding.

Tad: That's how it's really interesting Steve, I would love to do another segment talking more about that now that the growers have a little bit of a foundation into your philosophies and why this process is important. I think it would be wonderful to have you back on to talk about that.

Steve: We’ll go there another time.

Tad: You could write another book.

Steve: I don't think so. You younger people are going to work this stuff out, I'm 74 now, you know I'm just happy to get up now and feel good today and go out there and grow a few veggies.

Tad: Sure.

Steve: I really am not out to try the whole thing as much as I’ve already done, I'm kind of content at the moment. So what kind of loose ends have we lived in daily, we must have not finished all kinds of things in this conversation, where would you like to go?

Tad: Well you know, I think we covered a lot of it. I would love to follow up with you in another talk to talk a little bit more about sort of the connection between microbes and the soil food web and this idea of remineralization and how those two camps have sort of been butting heads in terms of their philosophies for many years, and then I would love to talk to you again about this foliar feeding idea and what your findings are with that as well.

Steve: And I would like to see a Logan Labs report on some of these deep soil beds that you've been running for 5 years and see what Logan says they look like.

Tad: I can show you a bunch of tests on that I think you'll find it really interesting.

Steve: I would enjoy seeing them and I’d like to talk to you about them.

Tad: Thanks Steve, I appreciate you taking the time to chat today all the way from Tasmania, don't forget to check out Steve's latest book “The Intelligent Gardener”, it's available on our website at www.kisorganics.com or on Amazon as a digital download.

You're listening to the Cannabis Cultivation and Science podcast, I'm your host Tad Hussey, stay tuned for future podcasts from other experts in the industry and don't forget there’s more information and resources available on our blog at www.kisorganics.com and if you enjoy these podcasts please take a moment to leave me a review and send me your suggestions and comments through our website contact page.